The Merlin Miniature Camera, and Developing 1940s Film

- Olly

- Aug 12

- 17 min read

Updated: Aug 13

Introduction

It began with a message from Maureen, a lady I had never met, though she knew my name through the local grapevine. I've visited the West Lancashire Light Railway for a number of years, and photographed their Santa Special last year (it's really well worth a visit, by the way!). Word had reached her from the volunteers there that I work with old analogue cameras, the sort of things which carry in their mechanisms the weight of decades, quite like the Railway's rolling stock. She explained that she had a family treasure that had belonged to her Uncle Herbert, a tiny Merlin miniature camera. It was last used, she believed, during his national service in India in the 1940s.

Inside the camera was a roll of film, potentially untouched for some eighty years. Her hope was simple: could I extract the film, develop it, and perhaps see what moments Uncle Herbert had captured before the world moved on? The camera has a small red window on the back which told me that the film was paper-backed roll film. It displayed number 5 – so at least 4 shots had been taken. How many were unshot? How many did a full roll take? I needed to find out more!

I have always thought of such requests as half photography and half archaeology. Each roll of found film is an artefact, its latent images long hidden, its chemistry altered by time, temperature, and the slow, invisible work of decay. Success is never guaranteed. Still, the very idea of working with a camera of this scale and history, and with film that had potentially travelled across time and continents was an intriguing challenge.

The Camera and It's Details

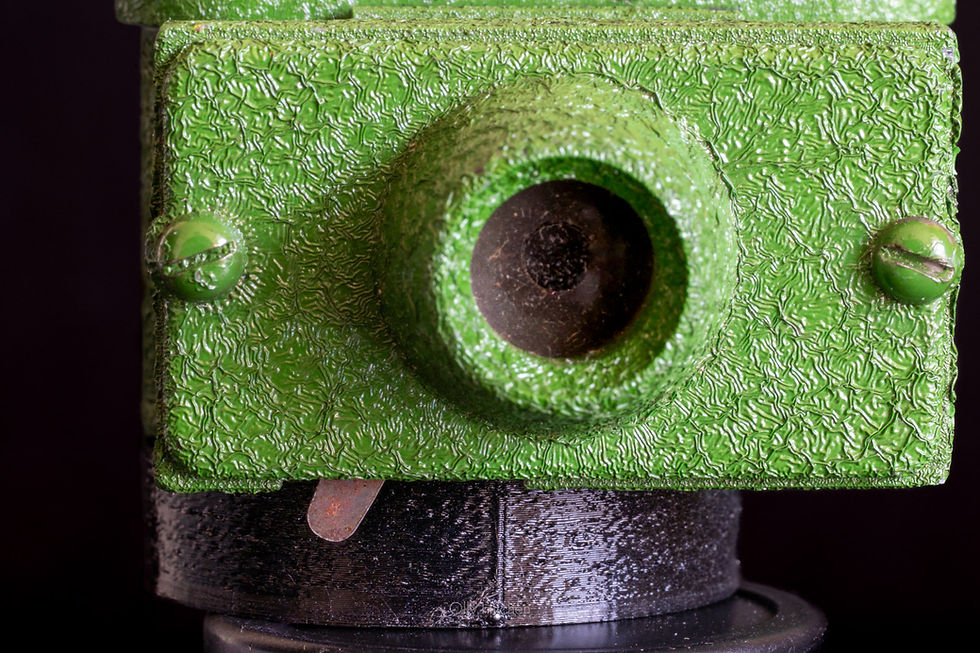

The Merlin camera is an object that asks you to look closely. Made by United Optical Instruments of Southend-on-Sea around 1936, it fits comfortably in the palm, measuring just 52 mm in height with the viewfinder folded out (it’s 38.7 mm with the viewfinder folded). It’s 46.7mm in depth, and a similar width, coming in at 49 mm. Its weight is 119 g, according to my kitchen scales, which gives it a surprising sense of solidity for such an ancient and small artefact. The body is cast metal, finished in a crackle-effect enamel that, in its day, could be ordered in black, green, blue, or red. This one, as you can clearly see is the rather interesting green. I must say, I absolutely love the colour of it!

It's operation is really simple. A fixed-focus lens, likely around f/16, sits permanently ready, paired with a single shutter speed of roughly 1/25 second. I measured the shutter speed as 1/32.4s which puts it 1/3 of a stop off the 1/25s mark. There are no exposure controls, no focusing rings. A flip-up wire frame viewfinder crowns the top, giving the photographer the barest of aids in composing a picture with the shutter release being in the form of a short metal lever, 5mm long underneath the lens.

The back of the camera hides another distinctive feature in the a tiny ruby-coloured window. Through this, the photographer could see frame numbers printed on the paper backing of the roll film. By turning the winding knob on the base until the next number was centred, they could advance to the next frame without double exposure. This was a common arrangement in the 1930s, and is still used by many medium format photographers today, but the Merlin’s film made it special. The film is a 20 mm-wide paper-backed roll, producing seven square frames about 18×18 mm each, half the width of a standard 35mm film frame most people are familiar with.

Today, this format is extinct. No film manufacturer produces it, and original spools are scarce, often found only inside surviving cameras. In many cases, the last film loaded remains there still, quietly ageing in the dark, as Uncle Herbert’s had done.

1930s/1940s Film

Finding out about the camera was one thing, but understanding what lay inside required a different kind of research. The Merlin’s unique 20 mm roll film was probably not made by United Optical Instruments themselves; instead, it was almost certainly cut and re-spooled from standard stock produced by major manufacturers like Ilford or Kodak’s UK branch.

The likely emulsion type was orthochromatic black-and-white, insensitive to red light, but really I had no idea. This made sense for a camera with a red window — the window could be used in daylight without fogging the film. Panchromatic film, which responds to the full spectrum, existed by the mid-1930s and was used by professionals for more lifelike tonal reproduction, but in the Merlin it would have been vulnerable to light leaks through the ruby window unless carefully shielded by the backing paper. At this stage there is of course no way of knowing however. If I knew the type of film, and it was orthochromatic then I could have simply used the red safe light in a dark room for all of this, but if it was panchromatic, and I used a safelight it would instantly ruin the film.

The film speed was probably around ASA 25–50 — slow by today’s standards but typical for snapshot films of the time. This slow speed worked well with the Merlin’s fixed 1/25 s shutter and small aperture. In bright daylight, the exposure would be about right, producing fine-grained negatives suited to small contact prints or small enlargements.

This balance of shutter speed and aperture lines up with the Sunny 16 Rule, a traditional guideline for estimating exposure without a light meter. I've written a guide on the Sunny 16 Rule, which you can find here. However, for quick reference, the rule states that on a sunny day with defined shadows, you set your aperture to f/16 and your shutter speed to the reciprocal of your film speed (for ASA 25, roughly 1/25 s). The Merlin’s fixed 1/25 s shutter and small aperture put it bang on this “ideal” for bright daylight. In sunny conditions, this meant exposures were about right for crisp, fine-grained negatives. In overcast weather, the Sunny 16 rule suggests opening the aperture (e.g., f/11 or f/8) to let in more light, but because the Merlin had no adjustable aperture or shutter speed, it could not compensate — the film had to rely on its latitude instead.

Film latitude is the amount a negative film can be over- or underexposed and still produce usable images. Snapshot films of the era typically had generous latitude, so even if the Merlin overexposed slightly in sun or underexposed in shade, the results were still acceptable, especially for the small contact prints people expected. This tolerance was crucial for a camera with no manual controls: all the exposure adjustment had to be handled by the film itself. As a result, photographers simply chose their days wisely, accepted that some shots would be less than perfect, and enjoyed the simplicity of a point-and-shoot experience decades before that term existed. At the end of the day, this wasn’t a heavy-duty professional camera. It was designed to be dropped in a pocket and a shot taken now and then. For example, Deardorff was a manufacturer of wooden-construction, large-format 4"x5" and larger bellows view camera from 1923 through to 1988 and were used by professional photographic studios. These would allow variable aperture and shutter speeds, as well as different lenses – a far cry from The Mini Magic Merlin Marvel!

When I extracted the film and loaded the custom reel, I saw that the surviving film in Uncle Herbert’s camera still bore a pink tint to the base, a tell-tale sign of an anti-halation layer. This coloured backing absorbed light that might otherwise scatter inside the emulsion and cause halation, a glowing halo around bright highlights. In normal processing, this dye just washes out. Here, after decades undeveloped, it remained for now.

Since the 1940s, however, even the best quality films would have undergone considerable chemical change. The latent images, the invisible record of light on silver halide crystals, would most certainly have faded. The base might have darkened with fog from background radiation or chemical instability. In practical terms, any surviving images would be faint, low contrast, and easily overwhelmed by chemical fog during development.

Developing 1940s Film

Developing all films, old and new, is a bit of a balancing act. When developing 1940s films, too short of a time and the image remains hidden; too long and the fog swamps what’s left. Too much agitation and you risk streaking on such a narrow, tightly curled film; too little and uneven patches may appear. I had adapted and 3D printed a 16mm film reel, and had loaded it in the dark, but I didn’t know if the curl on the film was strong enough to pull it out of the guide grooves on the reel.

I decided to use Rodinal, a developer first sold in 1891 and one I still use today for developing films from my Ensign Greyhound and which I used to develop the films from the West Lancashire Light Railway’s Photographers’ Day 2024. Its ability to work at very high dilutions makes it popular for so-called stand or semi-stand development — techniques that let the film sit in weak developer for an extended time with minimal agitation. This slow action can coax shadow detail from underexposed or faded negatives without blowing out highlights.

It’s better to use lower temperatures when developing old films to slow the process down. in ordinary development processes, each increase in temperature of 1c means need to reduce by 10% and vice versa. The lower the temperature the gentler the development process will be.

To start with, I gave the film a 10-minute pre-soak, changing the water halfway through which removed some of the pink anti-halation dye and softened the emulsion so the developer could penetrate evenly. I sometimes give films a pre-soak, Fomapan 100 for example turns the prewash a really cool looking green. There’s some debate on the internet about if it helps or not, and to be honest the times I’ve forgotten (or was being lazy!) I haven’t noticed much of a difference. However, with this film being so old, and of unknown film type I figured it wouldn’t do any harm. This film’s been sitting there for 80 years, another 10 minutes of cosmic rays isn’t going to harm it!

During the pre-soak, I mixed the 4ml of Rodinal developer into 600ml of tap water at 17c, and then poured it into the tank when the pre-soak had finished and developed for a total of 90 minutes. I went with the semi-stand approach, four gentle inversions at 30, 50, and 80 minutes. This refreshes the developer in contact with the film, reducing the risk of bromide drag or streaks, whilst keeping the process progressing, slowly.

After development, I stopped the process with a simple water bath (changing the water halfway through 45 seconds). You are generally advised to use a stop bath for this step, and I ordinarily use Kodak’s Indicator Stop Bath, but I went with water since the Rodinal dilution was so weak. I fixed the film for five minutes in Adox’s Adofix Plus, inverting the tank very gently for the first 60 seconds, and again 4 times every subsequent 60 seconds. I completed the development process and washed using the Ilford method: sequences of inversions with fresh water, increasing in number each cycle, first for 5 inversions, then 10, then 25. This ensures thorough removal of fixer without damaging the emulsion. The final step was a rinse in Aldi’s finest Magnum Apple green washing up liquid. Some people like to use a specific wetting agent, such as Ilford’s Ilfotol or Kodak’s Photo Flo, before leaving the negatives to dry overnight, hanging on my shower curtain rail. Thankfully I’ve got a very accommodating wife!

All the while, I tempered expectations. Even with the best technique, film from the 1940s is often too far gone to yield more than faint outlines or tonal patches. But as with any archaeological dig, the act of uncovering, of giving the material its best chance to shine, is its own reward... But did it shine…?

3D Printing a Custom Reel

Before any chemical work could begin, I needed a way to load the film. Standard 35 mm spirals were far too wide, and even 16 mm spirals would not hold the Merlin’s slightly larger 20 mm width without the film getting damaged or slipping under the guide rails.

The simplest and quickest solution was to adapt an existing reel. I imported the STL file for the reel into Fusion 360 and converted it from a mesh into a solid body for editing. Then, just below the screw thread of the central shaft, I made a clean cut in the model. I raised the top half by exactly 4 mm, creating a gap, and filled it with a precisely matched ring of material by extruding downwards using the join function. This extended shaft gave the film perfect clearance, allowing it to sit without strain or overlap.

The beauty of this approach was that it preserved the original threading and dimensions, meaning the reel would still fit the developing tank perfectly. After checking the model with a section analysis to confirm alignment, I printed it in matte PLA filament, cleaned it up, and hoped. I wanted to test it with a scrap strip of 35mm film, snipped from one of my bulk rolls, cut to 20 mm but I still wasn’t 100% certain of the dimensions of the film in the Merlin so thought I’d save my film. Thankfully, it loaded smoothly thanks to the small engineering change that made the entire process possible. If you’re interested, here’s a link to the reel which I adapted: https://www.printables.com/model/136957-pa-110-a-11016mm-film-development-reel-v2-paterson

By the time the research was complete, reel was ready and loaded, and the chemicals were mixed, it struck me how many layers of history were converging on this one small roll of film. A 1930s English camera, a wartime journey to India, a roll of silver halide emulsion long past its prime, and a 3D-printed reel designed on a modern computer. Whatever emerged on those negatives, the story was already worth telling.

How This Story Ends

When the development was done, I lifted the reel from the tank with a mixture of routine and anticipation. All along I had told myself not to expect too much, that the film might be entirely blank after so many decades, yet there it was, that quiet thrum of hope.

As I pulled the wet strip out of the tank, I noticed that it had loaded and stayed on the 3D printed reel just right. The film was only about 8 inches long, and as soon as I took it off the reel it coiled right up into a tiny curled roll once again. 80 years of curling wasn’t going to relax overnight! I gently clipped one end onto the clip hanging from a spare shower curtain ring, unwound the rest and added a second clip on the bottom to help it dry straight and to allow the water to run off. Under the bubbles of Aldi’s finest wetting agent, in the light I saw it: a latent image, faint but unmistakable. The very first frame on the roll had survived. The rest sadly hadn’t. I took a quick video and some terrible snaps on my phone, and emailed Maureen and Pete. Somehow, something had survived. I wrote, ‘Whilst it would have of course been great to see the other frames, considering the odds of even finding an undeveloped roll, in a very unusual camera with a niche and antiquated film format, of unknown emulsion type along with an unknown storage history I have to say I’m really rather pleased with retrieving a rooftop and a couple of trees! Really pleased indeed!’

Maureen and Pete are a lovely couple and we’ve chatted via email on a number of occasions now about this camera, Uncle Herbert, and what I was doing to see what we could uncover. Maureen let me know that:

Uncle Herbert was Herbert Senior (Pete’s mum’s maiden name, Herbert being her brother). He was born September 23rd 1929, and Maureen told me that Uncle Herbert was a bit of a recluse, he never married, looked after his mum in her latter years and even to his death had her last pension in an envelope having collected it from the post office and saying it ‘wasn’t his to open’. He was a joiner, loved making things, loved exploring new things - no doubt hence this camera. He was happy to have visitors provided they didn’t stay too long and he enjoyed his cats. What he didn’t like was having his photograph taken! The photo below is the only one in all of Pete’s mum’s photo albums which they inherited when she died earlier this year. As far as family collective knowledge goes, this was at the only family wedding he ever attended!

The next day I placed the film between two sheets of photo frame glass I use to digitise my 4x5 sheet film on a light panel and digitised the frames. Once scanned and processed, the first frame revealed itself more clearly. A rooftop was just visible through the shapes of what appeared to be two trees. It was not the sort of photograph that shouts for attention; rather, it whispered of a moment now far behind us. Given the camera’s history, I wondered if this was Uncle Herbert’s own house, perhaps a test shot taken when he first loaded the Merlin, the way a new owner might make a first photograph simply to try the mechanism as suggested by Maureen.

The remaining frames were less generous and require a huge amount of imagination. The last two exposures were my own, taken for curiosity’s sake, but neither registered even the feintest image, but this was unsurprising when you remember that film speed halves roughly every ten years, and these emulsions were already slow by modern standards. Over the span of eight decades, its effective sensitivity would have become almost negligible.

Given the right camera I think it might be just possible, but the light would have to be 256x stronger! Shooting at f16, and with our fixed shutter speed of 1/25 and fixed (assumed) film speed of 25 ASA (ISO equivalent in new money) then with each stop slower means doubling the exposure time.

1. 1/25 s → 1/13 s (8 stops left to go)

2. 1/13 s → 1/6 s

3. 1/6 s → 1/3 s

4. 1/3 s → 0.6 s

5. 0.6 s → 1.3 s

6. 1.3 s → 2.5 s

7. 2.5 s → 5 s

8. 5 s → 10 s

Sunny outdoors is about 100,000 lux (≈ “1 sun”).Eight stops more light is 256× that: about 25,600,000 lux (≈ “256 suns”).

Here’re a couple of easier ways to picture that:

A sky with 256 suns in it, and no clouds!

Solar concentrator focus (≈ hundreds of suns): Stand at the bright spot where a field of mirrors concentrates sunlight and you’re in the right in the middle. At ~256 suns, materials scorch or melt frighteningly fast”

Welding arc territory: A powerful arc welding arc viewed from uncomfortably close can reach multi-million-lux levels; it’s in the same order of magnitude as 256 suns. (And yes, that’s why welders need serious eye protection.)

Anyway, back to what the film tells us… The fact that this one frame survived at all is remarkable. I suspect it was saved by the way the roll had been wound. With the first frame tucked safely inside the tightly curled strip, it was shielded from the slow creep of light and air that would otherwise have destroyed it. Had the entire roll been exposed and wound fully on, perhaps more might have been preserved — but that is a question we can never answer.

With all of that work and research, cost, preparation, and time, I find myself more than satisfied. The odds were stacked against us. An unusual camera using an obsolete film format, an emulsion type I could only guess at, and no record of how the camera had been stored since the 1940s. That a single, distinct image emerged feels definitely like a small victory, the sort of win you only truly appreciate when you understand how close the whole thing came to being nothing but fog and shadows.

I sent the scans to Maureen and Pete, along with a slightly enhanced version of the rooftop frame and a wider photograph of the entire roll. In her reply she mentioned that she thought it could well be his home and that it might even have been the very first picture he took with the Merlin. Ultimately we will never know where this photograph was taken, India or the UK, or somewhere in between or around the sides, but that’s ok. In our modern world where information is instantly at our finger tips a bit of mystery and unknown is good for the soul.

Final Thoughts

Whilst some might consider the experiment a failure, I don’t — not in the slightest. Against the odds of time, chemistry, and circumstance, one frame was retrieved. In the face of such improbability, that single image feels like a victory. Some might ask, “Was it worth it?” My answer will always be yes. It’s always worth giving something a try, because you never truly know what you’ll discover until you do.

There’s something I’ve always found fascinating about photography. No matter how many people stand in the same place, pointing their cameras at the same scene, every single image will be subtly, and sometimes profoundly, different. A photograph is more than just a picture; it’s a one-of-a-kind imprint of a moment that can never truly be repeated.

You could return to the same location, stand in the very same spot, even frame the shot in precisely the same way, but it would never be identical. Light shifts. Shadows stretch. Clouds drift. Leaves stir in the breeze. People move. Even the air itself feels different. Something, however small, always changes, making each frame its own singular fragment of time.

What moves me most is the idea that the last time this exact moment existed was in the instant it was captured, and once it passed, it’s gone forever. Perhaps no one has seen it in this precise form for years, decades, or even centuries now. After the shutter clicked, that fleeting arrangement of elements was sealed away in time, waiting for someone to rediscover it in a negative, a print, or a digital file.

The digital age has given us access to an unprecedented flood of images, and while the number of shutter clicks grows exponentially each year, each photograph is still only a single, irreplaceable fragment of time. It is a moment plucked from the endless flow, stilled for as long as we care to keep it.

One day, perhaps years from now, someone will come across that image in an album, a hard drive, or a forgotten shoebox, and be the first to see that moment since the instant it was captured. For them, as for you, it will be as though time briefly opens a window, and the world holds its breath, allowing that one heartbeat to live again. In their hands, the moment in time converts to a photograph, morphing into a tangible link to the past for us, something real we can see and touch, and in that instant, history itself stirs, warm and alive once more.

If you know me personally, you’ll know of my love of history, and with that in mind I’m sure you can appreciate that for me the real treasure was in the project itself. The research, the making, the quiet moment in the darkroom, and the knowledge that for the first time in more than eighty years, the Merlin had been called into service again. Still, the idea of keeping the camera feels fitting. It has a story now that stretches from the 1930s or 1940s, across decades of silence, and into the present moment. A small quirky camera from Essex once again has something to say. We just need to find it a new voice and perhaps put some film through it once more.

As ever, thanks for reading!

Olly

Comments